Seeing What They Saw - Prints & Memory.

This post is about doubt. More specifically, doubts about missing something in a print no matter how hard I try to see it. Let me explain. When I begin studying a print – a political print, for example – I aim to place it into its original historical and iconographic contexts. I begin with the obvious. I unpick who or what is depicted. Then I turn to the asides, tracing any other prints it responds to, texts it shows, or anything else the print refers or alludes to. I now have the nuts and bolts and can make a good stab at locating the print in a moment of history. Then I turn to context. Why has this person or subject been depicted in this way at this time? What events does it respond to? And what do the print’s asides add to its point? This gives me colour and tone. Beyond that, I speculate. Why might someone have bought this? What might they have done with it? I make a case for my answers. But I am open about, and at peace with, those questions being irresolvable without hard evidence of how prints were used, a peace that historians of other printed sources must make, too. I now have enough material to write about the print. But then come the niggles. I’m missing something, aren’t I? What is that something? That for all my efforts to root the print in its original context, for all the evidence I present, I’m not seeing it as those who first saw it did. That there are things there, unspoken and unshown, that they would have grasped instantly but which remain unseen and unsaid to me.

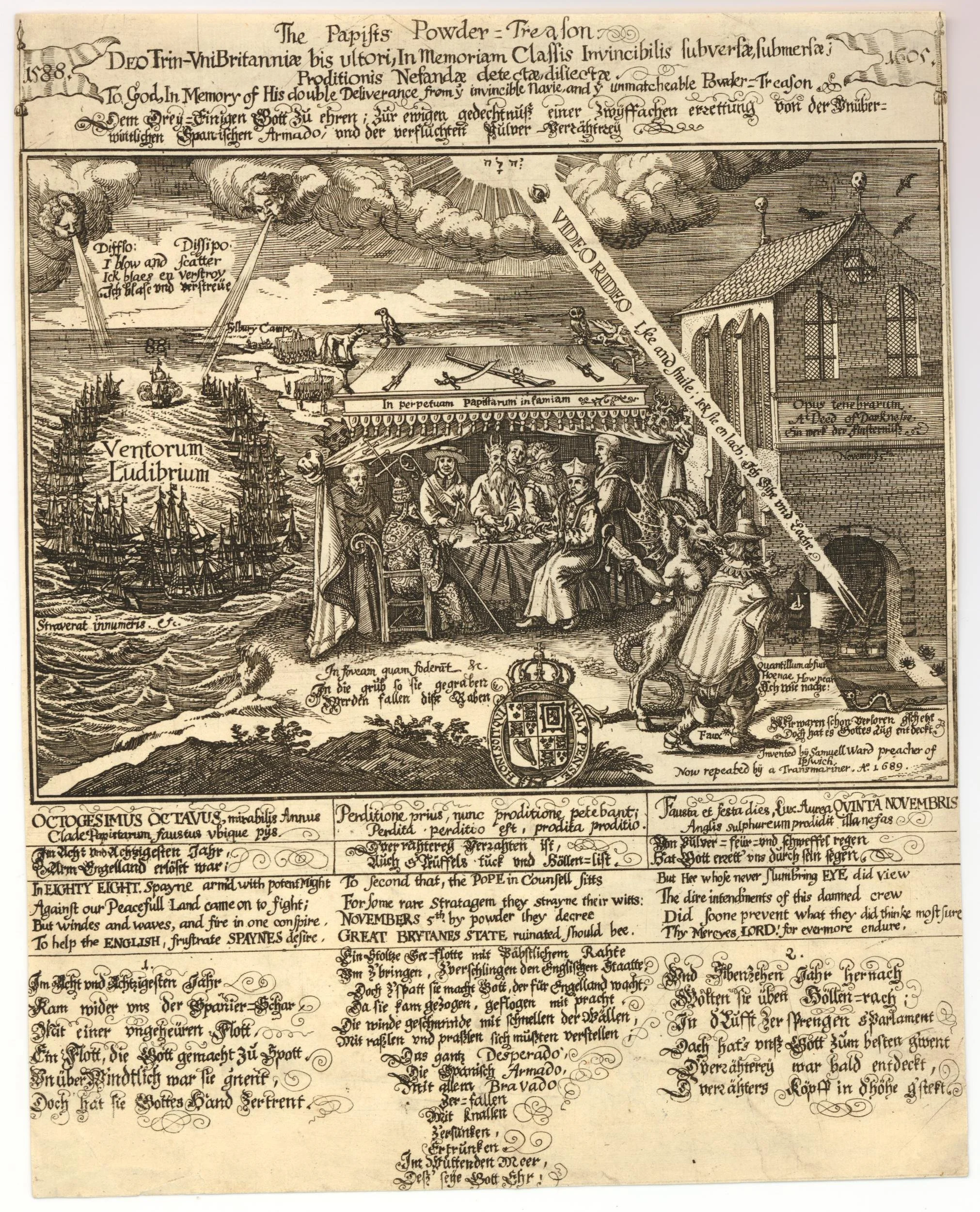

The Papists Powder Treason (1689). Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum,

But there are rare moments when you can grasp it. The Papists Powder Treason (1688), for example, was a print of many silences [Fig.1]. This print says more than it shows. It appears to be a simple celebration of two near misses in England’s past – the Armada (1588) and Gunpowder Plot (1605) – as providential deliverances from popery. In the centre, Antichrist is at work. A cabal of conspirators (the pope, the devil, a cardinal, a friar, and a Jesuit) plot England’s downfall. The scenes either side show their unfruitful schemes. On the left, a crescent of Spanish warships is about to be scattered by a fireship then destroyed by storms sent by God to save England, a point the inscription underscores, Ventorum Ludibrium; I blow and scatter. On the right, Guy Fawkes, lantern in hand, walks towards the cellars of the Houses of Parliament, intent on detonating the barrels of gunpowder shown by the open door. The divine eye exposes those intentions, piercing the scene from the tetragrammaton above, Video Rideo; I see and smile. The point is straightforward. Popery has plotted against England. Providence has foiled those plots. God favours Protestant England.

But why make that point in 1689, eighty-four years later? Context is all. The Papists Powder Treason depicted the Armada and the Gunpowder Plot, but it was not about them. The print was concerned with what it did not picture: the ‘Glorious’ Revolution of 1688/9. That event – which deposed the Catholic James VII and II and replaced him with his daughter Mary II and her husband, the Dutch Stadholder William of Orange, who would become William III – was sold by the crown and the Whigs as another deliverance from popery. William made that case in his ‘Letter to the English People’, which presented James’s toleration of Catholics as a step towards popery and arbitrary government. And his landing at Torbay on 5 November 1688 underlined it. That The Papists Powder Treason was really about 1688/9. That it commemorated without showing what was being commemorated would have been clear to its seventeenth century audience, and more powerful for being unshown and unsaid.

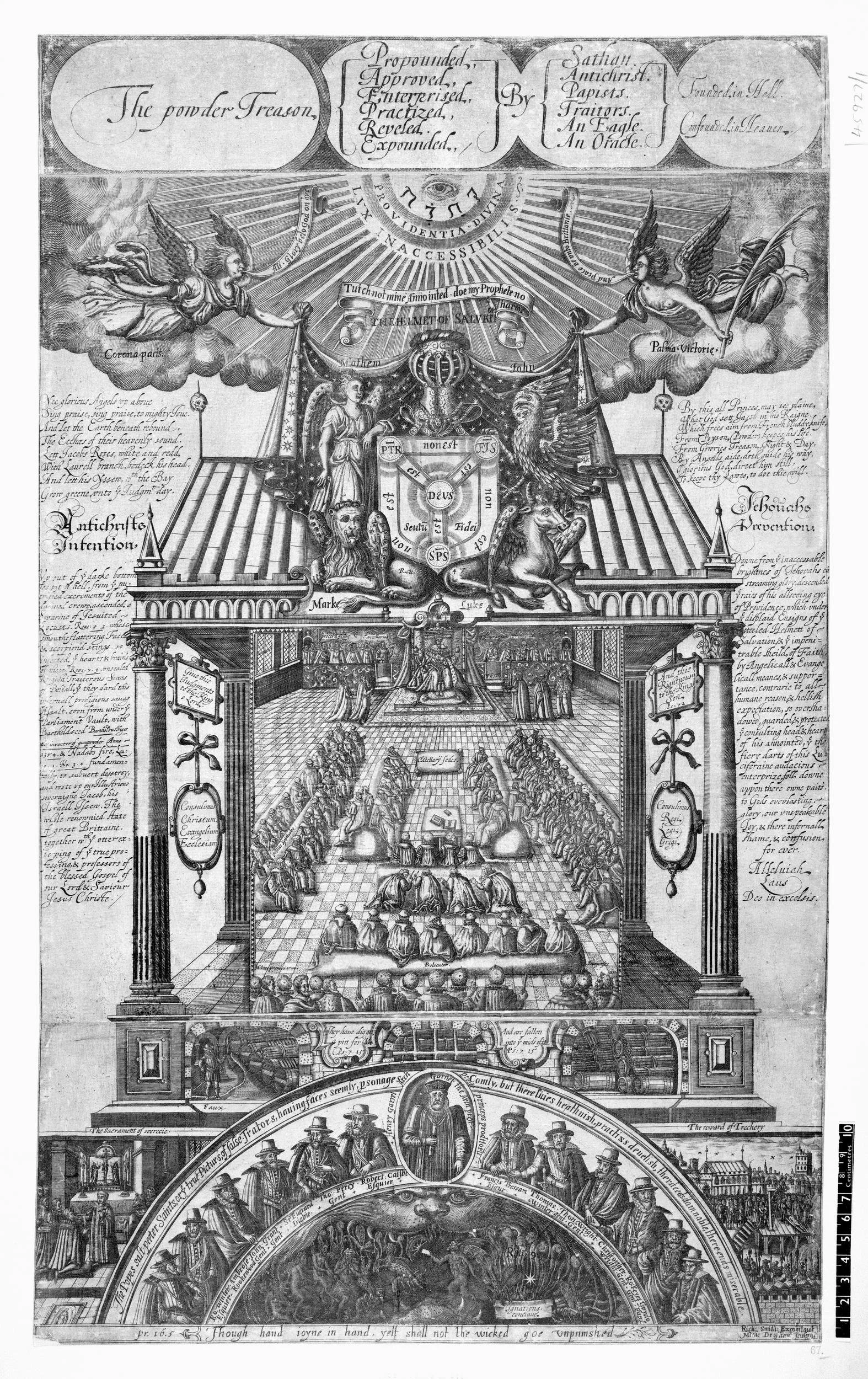

Fig 2. Samuel Ward, The Double Deliverance (Amsterdam, 1621). Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

The absence intrigues. What lies behind this image? And how might we see it as it was seen in 1689? The inscription points us in the right direction by nodding to the print’s controversial history: “Invented by Samuel Ward preacher of Ipswich/ Now repeated by a Transmariner. AO 1689”. Samuel Ward (1577-1640), Jacobean puritan and controversialist, had been dead for nearly half a century by 1688. He lived in popular memory because in 1621 he designed one of the most infamous prints of the seventeenth century, The Double Deliverance [Fig. 2]. Ward was arrested for designing The Double Deliverance, which had offended the Spanish Ambassador at the court of James VI and I, Diego Sarmiento de Acuña, Count Gondomar, who objected to the inclusion of Philip III of Spain in the print’s central scene, the popish cabal, In perpetuam papistarum infamian (the papists’ perpetual infamy). Philip’s depiction as conspirator referred to the Spanish Match (1614-23), James’s attempt to forge an Anglo-Spanish alliance by marrying Prince Charles to Infanta Maria Anna, which horrified hotter Protestants in Jacobean England. The Double Deliverance made a political use of the memory of 1588 and 1605 as pivotal moments in English history, warning that England was falling victim to another popish plot. Ward’s triptych presented the Spanish Match as equally dangerous as the Armada or Gunpowder Plot and implied that by pursuing it, James was snubbing providence. The print was one part commemoration, one part polemic.

Fig. 3. Richard Smith, The Powder Treason (1615). Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Ward denied all of this, of course. He claimed The Double Deliverance was just a memorial print. This was a plausible defence. There were plenty of anti-Catholic memorial prints in the early-seventeenth. Richard Smith’s The powder treason (1615), which celebrated ‘Jehovahs Prevention’ of ‘Antichrists Intention’, is a good example. The eye of God overlooks a canopy under which James is seated in Parliament, surrounded by the Privy Council, peers, and bishops. In the vaults Fawkes is ready to detonate barrels of gunpowder to complete a conspiracy shown to have been hatched in the mouth of hell and implemented by 12 ‘popish’ apostles (the plotters and the Jesuit Henry Garnet). The print’s design aped stone monuments. It was a memorial intended to prompt owners to offer praise to God for his deliverance. [Fig. 3]. No Plot no powder (1623) was published after the ‘providential’ collapse of a Catholic chapel in the house of the French ambassador in Blackfriars, London, during a sermon by the Jesuit Robert Drury in October 1623. The print presented the disaster – which killed 90 people – as an act of divine vengeance for Jesuit’s being active in a godly kingdom, the hand of God shooting a beam of light to silence Drury’s by piercing his heart [Fig. 4]. Ward’s Double Deliverance, then, was a variation of a theme. It used commonplace providential imagery to turn commemoration of 1588 and 1605 into a protest against the ‘popery’ emerging in the Stuart crown. James’s refusal to intervene on the side of Protestant Europe in the 30 Years’ War, his marriage to a Catholic wife, the wave of Catholic conversions at his court, and the growth of Arminianism in his church, began a fear of Stuart popery that would be central to English politics in the reigns of Charles I, Charles II, and James VII and II.

Fig. 4. No Plot No Powder (1623). Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

The Double Deliverance’s imagery reappeared regularly across the seventeenth century. We find it on the titlepage of Christopher Lever’s The history of the defenders of the Catholique faith (1627), in which the true church tramples on the false church comprised of devil, pope, and cardinal. The true church is flanked by Elizabeth I and James VI and I, who hold banners showing images after Ward’s print depicting the Armada and Gunpowder Plot, respectively. [Fig.5]. By the 1630s the Double Deliverance began to bear associations with opposition to the Stuart crown and church as agents of ‘popery and arbitrary government’. Ward’s imagery fell foul of the Laudian church’s aim of dampening the apocalyptic anti-Catholicism of earlier English Protestantism as it moved to reform and moderate the Church of England. Laud’s officers removed aggressive memorials to 1588 and 1605 were removed in parish churches. In this context, new uses of that imagery took on new meanings. A depiction of the Gunpowder Plot after Ward appeared on the frontispiece to John Vicar’s The quintessence of cruelty (1641), which had been banned by Laud’s censors and was only published after the fall of the bishops during the Long Parliament. Vicars’ text pointed to his publishing his memorial anti-popery as an act of deliverance – Laud (and his church) was part of the ongoing popish conspiracy.

Fig. 5. Christopher Lever, History of the Defenders of the Catholique Faith (1627).

The anti-Stuart bent of the imagery continued forty years later, when the central cabal scene of Ward’s print was used in prints produced during the Popish Plot and Exclusion Crisis (1678-82). The Happy Instruments of England’s Preservation (1681) collapsed three years of (imagined) ‘popish’ intrigues into one conceit centred around the cabal scene after Ward’s Double Deliverance [Fig. 6]. Above the cabal sit the four ‘witnesses’ of the Popish Plot, lauded by angels, one of whom holds the English crown they have saved through their discoveries. This print was published in April 1681, shortly after Charles II had dissolved the Oxford parliament, the final parliament in which the Whigs pressed for reforms in the constitution and the church to save England from ‘Popery and Arbitrary Government’, chief among them being moves to exclude the Catholic James, Duke of York, from the throne. Charles II’s dissolving Parliament (he ruled without it until the end of his reign in 1684) was easily spun as a refusal to protect England from Catholic conspiracy, a mark of the popish sympathies and arbitrary tendencies of the Stuart crown.

Fig. 6. The Happy Instruments of England's Preservation (1681). Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

The point I am making is simple. Those who saw The Papists Powder Treason [Fig. 1] in 1688 would have seen a lot more than the print showed. They would have understood that the print tied the 1688/9 Revolution to a century old tradition of providential anti-popish imagery. They would have grasped the associations of that imagery, the 70 years of protest against Stuart ‘popery’ that the print brought to bear in a new political context, styling 1688/9 as a ‘Protestant’ and Whig victory at a moment when fundamental aspects of England’s politics – hereditary monarchy, passive obedience, the constitution – were contested. In short, they would have grasped that The Papists Powder Treason was as concerned with England’s deliverance from the Stuarts as it was England’s deliverance from Rome. The print’s central point was unpictured but not unseen.