What’s It All About, Then?

“Don’t get me wrong, they’re interesting”, said the student, eyeing a pile of prints I’d suggested might be the basis of her dissertation. “It’s just…..I wouldn’t know what to do with them”. She leafed through the prints, all of which fell within the bounds of her dissertation topic – ‘Early Modern Culture’ – treating each carefully before placing it on the desk in front of the rest of the seminar. Heads turned and eyebrows raised as images of gossips, drunks, gamblers, and giants began to cover the table. Scenes of rioting caused a couple of students to lean over, those of monstrous births led some to stand to get a better look. A submarine was met with surprised smiles, portraits of recently deceased children, silence. The odder the print, the longer they looked. Isaac the Famous Grinner provoked intrigue and irritation (Figure 1). “What’s he grinning at, anyway?” said one student, frowning.

Figure 1: Isaac the Famous Grinner (1711). Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

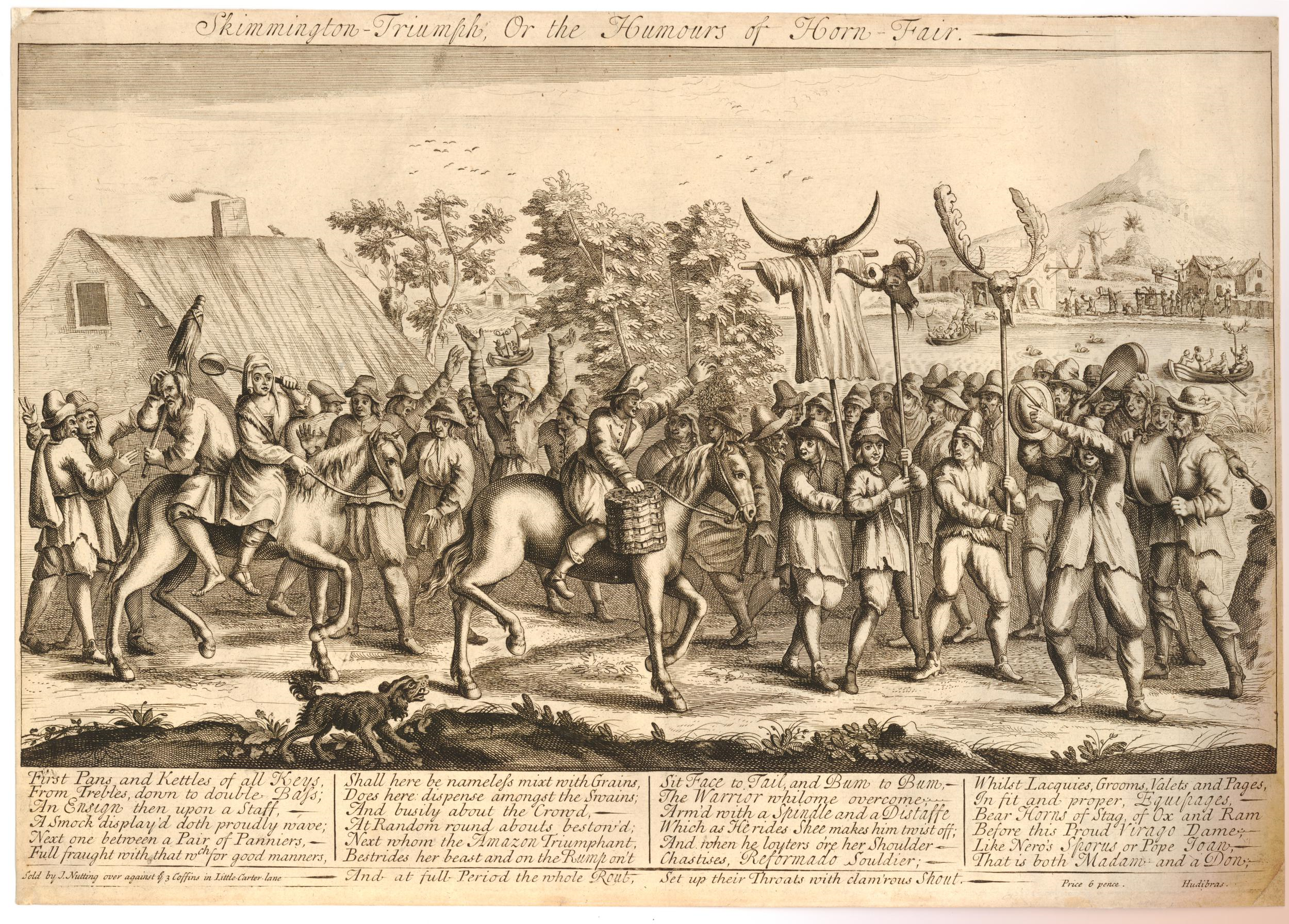

The students’ curiosity was tempered by suspicion. “Weird”, said one student, pointing to a print of a ‘Bear-faced Lady’, to nods of agreement from the room (Figure 2). “Wouldn’t want them on my wall”, added a second, chuckling. Our student was more intrigued. “There’s something here though, isn’t there?”, she said to the room, staring hard at one print, “they offer a different way into the past”. She paused; we waited. “I mean, why would someone want to buy this?” She held up an A3 reproduction of the Skimmington-Triumph, Or the Humours of Horns Fair (1711), in which villagers shame a cuckold and his shrewish wife by parading them on horseback while banging pots and pans to publicise their humiliation. “It’s weird to us, but it obviously meant something to them. If we could get at that ‘something’, I think we’d have a foothold in some small piece of their culture”.

Figure 2: Bear-faced Lady (c.1680-1700). Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 3: Skimmington-Triumph, Or the Humours of Horns Fair (1711). Copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

This was a good point, and the rest of the seminar knew it. We – me in particular – wanted to hear more. “Yes, I can see that the images could be useful, and so interesting” she continued, gathering up the prints from the table, arranging them neatly, and handing them back to me, “But I need to work with sources that are a bit more…..solid”. Oh well, I thought, knowing that she was going to write an excellent dissertation whatever the topic, close but no cigar. And then, the killer question. “What do you think?”, asked the Serious Student’s friend. “What do images like this tell us about the past?”

I floundered, talking lots but saying little to try and hide that I didn’t really know, either. I came clean, the students laughed, and then we had the sort of discussion that reminds you why you wanted to teach in the first place. I asked the student what she meant about prints not being solid sources. She frowned. “I want to use sources that give me a steer”, she said, “ones where I have a sense of why they were produced – like an account book or a letter – and what they might mean”. Her friend, nodding quickly, was more direct. “We’ve only ever used written sources”, she said, “and that’s what I’m comfortable doing: gutting a text”. Historians, the room agreed, like words. Other types of sources – images, objects, artefacts – were interesting, but they made the students uneasy and unsure. They felt that had neither the knowledge to unpick them, nor the know-how to use them to unlock the past. As I left the seminar, one student’s words stuck in my ears: “This stuff just doesn’t seem like my corner of the wood”.

Many historians think that the ‘stuff’ of visual sources is not their turf. Although we celebrate interdisciplinarity, and although the ‘Material Turn’ has told us new and exciting things about early modern history, ‘stuff’ still feels like it belongs to someone else, the property of Art Historians or Museum Curators. My project, ‘British Printed Images to 1700: Integrating visual sources into historical practice’’, was conceived in response to that unease (and those students). As I explored the ‘British Printed Images to 1700’ archive, I was staggered by the sheer number of prints produced in this period (which is well into the thousands). Why, I wondered, do historians not make more use of them? And what would the effect be on our understanding of early modern Britain if we did?

There is a danger of overstating my case. Prints have been studied by historians, often with dazzling results. The political print is a good example. Alastair Bellany, Tim Harris, Mark Knights, Helen Pierce, Kevin Sharpe, and Alexandra Walsham have shown us how to interrogate visual sources to enrich our understanding of Jacobean politics, the Civil Wars, the Exclusion Crisis, the 1688 Revolution, and the first age of party. Their research integrates political prints alongside more traditional sources (state papers and court records) and sources of popular opinion (pamphlets, newsbooks, plays, and ballads) to construct rounded accounts of politics in Stuart Britain. But political prints only make up a fraction of a rich archive with much to tell us about other aspects of history. About how early modern people understood the natural world, for example, in their portrayal of landscapes, plants and vegetation, animals and birds, and the human body. About gender, in their masculine and feminine dress, gesture, and behaviour. About place, in the depiction of urban spaces, courts, houses, and alehouses. About intellectual history, by showing how ideas were represented. And about much, much more. A glance at the archive shows that histories of race, ethnicity, the sea, childhood, and work might be enriched by turning to visual sources.

What do images add to our knowledge of those aspects of early modern history? What do they tell us about the past that other sources do not? As the student said: there is something there. My concern in ‘Integrating the Image’ is to work out what that something is. To think about how images offer us, in her words, “different ways into the past”.

In this blog, I’ll be floundering towards some answers.